F*@#ing reticence

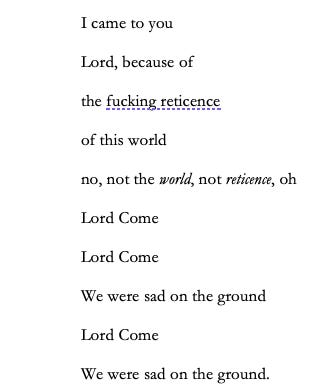

Emily Dickinson wrote, ‘I dwell in possibility’. For Dickinson, as for many poets, possibility resides in the gaps, the silences, the places where language cannot reach. While reticence and the unsaid hold endless possibilities, the white space around words can be unnerving. Jean Valentine’s poem, ‘I came to you’, captures the unsettling aspect of reticence:

This poem cries out with rage and with longing for revelation.

Reticence can be painful; at least in this context. There is an ache for some response from God, for openness, for knowledge. For the transparency of language. But then the speaker seems to realize, as can be seen from the words ‘no, not the world, not reticence, oh’ that the language in the crying out is not the right language. The speaker means something else. It is not the ‘world’ that she is complaining about and it is not ‘reticence’ that is the source of her anguish. But then what is it? More longing comes from that question. But there is no more rage. Just sadness (as can be seen from the repetition of ‘We were sad on the ground’), which represents a kind of transformation and revelation in the poem.

This reading suggests that Valentine’s account of reticence is ambivalent and shows a frustration with both reticence and language. Although language fails, let’s not romanticize silences, Valentine seems to be saying. Silences can leave us bereft in some instances. The white space on the page betrays us even as it holds endless possibilities.

[painting: Mrs Edith Mahon by Thomas Eakins]

there is a silence though that isn't reticent - I imagine this is what Jean V is longing for - the silence of peace, of love beholding, of being seen, etc...