Sharon Olds is famous for writing with unflinching intimacy about profoundly private moments but in a recent session I taught about her work we focused the discussion on her literary influences, formal strategies, and the ideologies behind her work. This approach to Olds breaches expectations. It was exhilarating and almost transgressive to speak about her poetry in this way.

‘The problem with teaching poetry’ Charles Bernstein has written ‘is perhaps the reverse of that in other fields: students come to it thinking it’s personal and relevant, but I try to get them to see it as formal, structural, historical, collaborative, and ideological. What a downer!‘

Fortunately, for my students, the experience of centring the discussion around Olds’s formal and structural strategies, historical context, and her ideas and influences was not a downer at all. We spoke about her

· line beginnings and endings

· commitment to the simile

· relationship with the four-beat line

· choice to write most of her poems in one single stanza

· ideological project

· political sensibility

· literary influences

For a discussion on line endings and beginnings (Olds prefers not to call them ‘line breaks’ as the term implies that poems are blocks of prose that need to be broken up) see this video where she describes how in her mind a poem is like a pine tree: the left margin is the trunk and the right margin words are the pine needles hanging. She even does a physical demonstration of this, her back facing the audience. And if you want to know what the space is to the left of the ‘trunk’ watch the video…

(For snippets on some of Olds’s literary influences and ideological stances see my previous substack posts.)

Regarding the simile, Olds has said that she ‘has never been comfortable saying definitively, as metaphors do, that something is something else.’ Sam Anderson wrote in the profile on Olds in The New York Times Magazine that ‘She ascribes this to her terrifying childhood experience of religion, the idea that blood was wine, that body was bread.’ Because of this experience she prefers the comforting distance of the ‘like’ and ‘as’. Seeing the world through a simile mindset as opposed to a metaphor mindset reflects a sensibility of ‘radical interconnection’: everything is connected yet all things are allowed to stay themselves. Connection is critical but so is separation.

This reminds me of the riddle of the Kotzker Rebbe (1787-1859) who famously said the following: ‘If I am I because I am I, and you are you because you are you, then I am I and you are you. But if I am I because you are you and you are you because I am I, then I am not I and you are not you.’ In order for something or someone to be themselves, some form of non-merging is essential; a separateness is crucial.

In fact, this brings us to a discussion of how Olds has said that her poems are ‘apparently personal’, a term she has used since the beginning of her career. This is not just about privacy. Olds is calling attention to the separateness between the poet and the poem and a necessary distance between the reader and the poet. It’s an aesthetic and ideological stance. As she told The New York Times: The ‘I’ is a character and the people in poems are the speaker’s vision of those people.

On the other hand, a high school student once said to her that they would feel betrayed if they thought she had made up the stories in her poems, they would be angry if they thought the poems were not based on her life. Olds was surprised but agreed and applauded the student and told them that they were right, that she would feel exactly the same way.

It’s a paradox: Poetry is not personal. We must assume that it is personal. It is never personal. It always is personal. If you can hold each of these statements in your mind simultaneously and embrace them all as equally true then you may begin to know what poetry is.

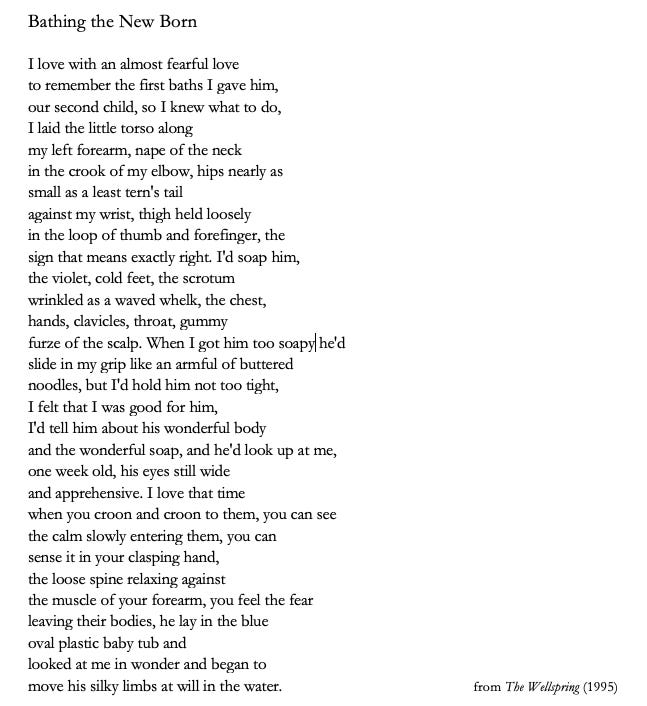

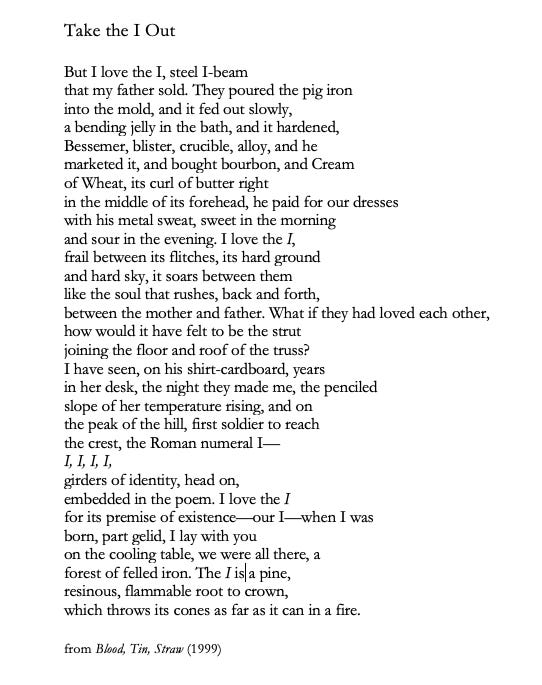

See two poems below. One ‘I’ poem and one poem written after being told to take the ‘I’ out of poems. In the ‘Bathing the New Born’ notice the similes (‘he’d / slide in my grip like an armful of buttered / noodles’ ) and the line endings, especially enjambed lines that end with words like ‘as’ or ‘to.’ And then enjoy the speaker’s embrace of the ‘I’ and her tone of defiance in ‘Take the I Out’.

I love this sleeves-rolled up look at how Olds works her magic. Her response to a young reader’s need for authenticity reminds me that she also said, “if you raise a question in a poem, it must be a genuine question you want to explore with the reader.”