The unsaid. This aspect of poetics is dear to poets.

Adrienne Rich argued that ‘what isn’t named is often more permeating than what is’. In her essay ‘Disruption, Hesitation, Silence’, Louise Glück wrote, ‘I am attracted to ellipsis, to the unsaid, to suggestion, to eloquent, deliberate silence. The unsaid, for me, exerts great power: often I wish an entire poem could be made in this vocabulary’.

In a letter to her aunt, Emily Dickinson wrote that ‘Saying nothing, My Aunt Katie, sometimes says the Most’. John Keats famously put it this way: ‘Heard melodies are sweet but those unheard / Are sweeter’. Kristina Marie Darling writes persuasively about the thirst for absence and for the traces of presence in the white space of a poem, when she discusses how ‘It is in these liminal spaces – the glowing aperture, the tentative sigh, the pause for breath – that the rules of language no longer hold, and anything becomes possible.’ Stéphane Mallarmé even attributed metaphysical status to ‘the very silence of the poem [. . .] its blank spaces’.

Jean Valentine viewed silence in poetry as richer than words: ‘The kind of silence I want to talk about is so much more full than language, so it’s hardly holding anything back; it’s that you cannot give it voice because voice is so much less.’[7] For Valentine, it is language that says little and reticence or silence that is ‘full’.

When editing my poetry collection Morning Prayer for publication, I too longed for textual silence. Or at least reticence. I noticed that the poems became more dynamic, generating energy, when I removed words from them.

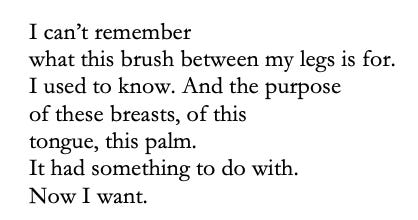

For instance, when editing the concluding poem, ‘Afterwards, Eve’, something told me that I should cut off the last line mid-sentence. I would not have been able to articulate the reason, but I instinctively felt that the white space after the poem ended transmitted more information than language could have provided. Here is the seven-line poem after cutting the last line, ‘Afterwards, Eve’:

At the time of this edit, I was not conscious of why I cut the last line. For me, and for many poets, the writing and editing comes from an unconscious place.

When I was studying for my MFA in poetry at Sarah Lawrence College, my teacher Marie Howe told me a story which validated my experience with editing ‘Afterwards, Eve’. When she was working on her poem ‘What the Angels Left’, she brought it to her teacher, Stanley Kunitz. He studied it for some time and then crossed out the last two lines. She railed against him, arguing that the last lines artfully articulated the metaphor, captured the healing from the grief imagery in the previous lines, and clarified the narrative. Later, however, she found wisdom in Kunitz’s edit: the wordy explanation at the end obscured meaning while the white space in its place communicated meaning. But she herself could not explain how that process had occurred.

One thing I did understand was that words were not enough, or as T. S. Eliot’s Prufrock puts it, ‘It is impossible to say just what I mean!’ In addition to reflecting Prufrock’s frustration, Eliot was confessing the fact that many poets feel their primary medium fails them. What can a poet do when they cannot say just what they mean? When words fail? In order to address these questions, I began to look to the work of other poets for answers. Mary Oliver, in her essay about writing poetry, provided a clue regarding the role of reticence in the production of meaning:

Modesty will give you vigor. It keeps open the gates of prayer, through which the mystery of the poem streams on its search for form. Just occasionally, take something you have written, that you rather like, that you have felt an even immodest pleasure over, and throw it away.

Like Oliver, I too found that employing ‘modesty’ in the writing process opened my poems to a power beyond my control as a poet, as if a light from another source were allowed in when ‘modesty’ was employed. In a private conversation with the American poet Galway Kinnell, he similarly suggested to me that he thought the sounds, meanings, and rhythms taken out of a poem in the revision process haunted the page like ghosts – shades of their presence could be sensed, reverberating off the words still present in the poem. The act of cutting, of editing, of employing modesty can, perhaps counterintuitively, be so powerfully generative that it may feel almost magical or supernatural to the poet. While the metaphor of the supernatural may be appealing, it does not fully illuminate the inner working of this poetics, nor does it allow for the poet to feel in control of their own writing. Kinnell’s proposition and all of my musings above reflect a belief in the presence of absence, in the power of the unwritten. Even so the question remains: how can meaning be found when it is not there?

I plan to speak to this question in the next post.