In today’s post, I discuss a poem from my forthcoming collection, Boat of Letters. And I explore my writing process and analyse the poem. I then read and discuss a poem I had in the back of my mind when writing mine.

My writing is intimately intertwined with my reading. I identify with the lines by Polish poet Adam Zagajewski that rejoice in this aspect of the artist’s process:

In other words, art generates art. And poems breathe out the language, rhythms and reticences absorbed from poetry.

T. S. Eliot put a cynical edge on this when he wrote, ‘Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal; bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better.’ Harold Bloom pushed this approach further when he developed his theory in The Anxiety of Influence that ‘The meaning of a poem can only be another poem’, and argued that poets are anxious, jealous and conflicted about the impact of poems they have read on their work. However, I take my cue from Zagajewski in this area, and not from Bloom or Eliot: not all poets experience conflict as their reading is absorbed and reborn into their own work.

With humility and awe, in ‘My Books’, Jorge Luis Borges wrote:

This reminds me of something the poet Catherine Barnett once told me: she prefers to talk about and teach her own poems rather than the poems she loves by others – she finds it ‘embarrassing’ to discuss her favourite poems by other poets – those poems feel so personal and intimate, revealing more about her than her own work.

No matter what approach you take, these quotes from Zagajewski, Eliot, Bloom, Borges, and Barnett all suggest that poetry by others is crucial for poets. Stanley Kunitz once said to me, ‘Poets needs poets like children need parents.’

When I wrote my poem ‘Snakes and Ladders’, I had Stanley Kunitz’s vision for poetry in mind: he said, ‘I dream of an art so transparent that you can look through it and see the world’. I probably was also unconsciously thinking about Dorianne Laux’s poem ‘On the Back Porch’ when writing this poem which embodies what I think Kunitz had in mind.

Here is her poem:

The narrative and the emotions involved in this narrative are clearly laid out: a woman’s family makes dinner while she goes out to the back porch and waits ‘until what I love / misses me, and calls me in.’ The poem seems to reflect Kunitz’s dream of the transparency of poetry.

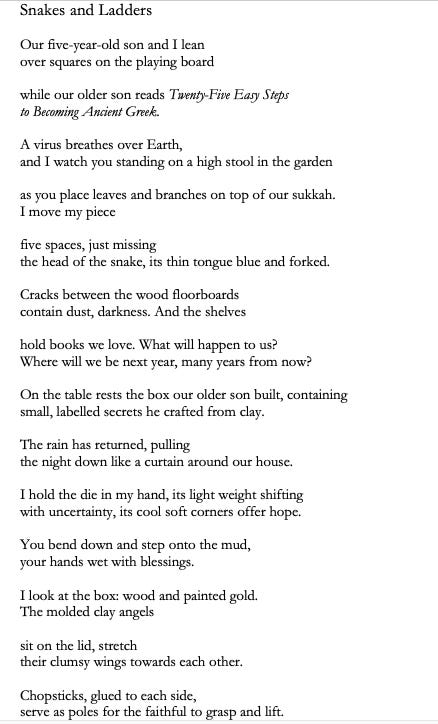

When I began to take notes towards the beginning of my poem ‘Snakes and Ladders’ I wanted to reflect the same sense of calm and contentment with clear images and details. But I also wanted to add uncertainty. One way I did this was to write with more enjambed lines. Laux’s poem has more end-stopped lines which can communicate security, clarity, and tranquillity. Also, the gaps and silences in my poem convey anxiety about the attachments in the poem. This tension is sometimes explicit but more often implicit. Here is the poem:

The description of this family moment is transparent – the narrator plays a board game with her son while the other son reads a book and the husband builds a sukkah in the garden.[1] The story of this moment is laid bare in simple, grammatically correct sentences. The poem, recounting a lazy family scene, with allusions to an uncertain future, is not obscure and it does not in any obvious way seem to conceal any steps in the narrative. It is not aggressively reticent; in fact, it seems to transgress the poetics of reticence. However, the poetics of reticence is at work.

An example of a moment in the poem where reticence seems to lapse appears when the word ‘love’ is used in the 13th line: ‘the shelves / hold books we love.’ This line seems to explicitly tell the story of the speaker’s emotional narrative as it contains such a familiar and large word to describe how a mother and wife feels about her family. Yet there is a distance which might not be immediately apparent. In this line she is not talking about her family; she is talking about books. And she doesn’t write ‘I love’ but rather ‘we love’, which creates a certain aloofness from the self. This hiccup, this bump or projection of her love for her family, coming from ‘we’ rather than I, and onto the books (which she also apparently loves) is a form of reticence: it is a way for her to not say directly how she feels about her family. And this not-saying is what creates a forcefield of energetic meaning in this poem with its seemingly narratively and complete lines. In addition, the use of the word ‘love’ here also calls attention to the lack of such language elsewhere in the poem.

This same approach takes place in Dickinson poems that employ emotive language; for instance, when Dickinson begins a poem, ‘After great pain, a formal feeling comes –’, the word ‘pain’ is used and then no such language appears in the poem again. The poem is reticent about the speaker’s emotional narrative after the word ‘pain’ is used. This lack of emotional narrative coming after ‘pain’ causes the sounds and silences after that word to sting and sing with that word’s message and meaning, much more so than if any more emotions were named in the narrative. The spaces between words – the narrative gaps – created by the absence of the emotional storyline bathe in the word ‘love’ and glow with its meaning without using the word or even similar words again.

The poem also contains a tension around the word ‘love’ because of how it contrasts with a sense of darkness, a narrative that hovers underneath the poem’s surface. The title of the poem, which refers to a commonly known board game, includes a hint –‘Snakes’–towards what lies in the poem’s silences. While the first few lines seem innocuous in their language and description, the mention of this inauspicious animal registers ill-omen. If the reader did not consciously pick up on this hint then it will become clear in the fourth line of the poem: ‘A virus is breathing over Earth’. While this line holds menacing information, the mention of a threat ends there and leads to a mild, even grounding, next line: ‘and you stand on a high stool in the garden’. The alarming image of the virus is breezed over and sharply contrasts with the observation of a ‘you’ (presumably the speaker’s beloved), suggesting that the speaker cannot dwell on what is ‘breathing over the Earth’ for too long. The speaker is both strong enough to acknowledge a threatening reality but also vulnerable as she does not wish to spend time with the material just presented. This is the first place where the poetics of reticence creates a charge in the poem.

When the speaker mentions that the ‘Cracks between the wood floorboards / contain dust, darkness’, again a sense of foreboding is conveyed. The mention of darkness leads to the question: what lies in the darkness? Unknown stories from the past and how those stories have impacted this family? An uncertain future? The poem does not speak to this line nor does it answer the questions that the statements about the darkness raise. Again, this breezing over suggests that perhaps the speaker is too fragile to spend time with those moments of darkness. It also seamlessly creates a gap in the narrative: the reader doesn’t learn any more here about this family and what lies in the darkness of their lives. The family represents an ‘other’ which will remain mysterious, unspecified, even mythic. These characters cannot ever be fully known. While the poem seems to be revealing in some ways, ultimately its story is private, reticent. Reticent to the reader and to the family it describes. And to the poet who wrote it.

[1] A sukkah is a temporary hut constructed for use during the week-long Jewish festival of Sukkot (which takes place after the Jewish New Year Rosh Hashana and holy day Yom Kippur). It is common for Jews to eat, sleep and spend time in a sukkah during this week.