Jacques Derrida noted, ‘I don’t want to say or cannot, the unsaid, the forbidden, what is passed over in silence, what is separated off… — all these should be interpreted’. Derrida and other post-structural critics such as Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault were interested in the gaps on the page; however, since the post-structuralist project was to show how meaning is cancelled in texts, they argued that silences annul meaning. Their mission was to challenge the assumption that texts are self-sufficient structures with inherent value. Therefore, they also saw silences in texts as eradicating or swallowing up any sense of truths or genuine communication. According to them, both words and silences undo meaning just as they seem to construct it.

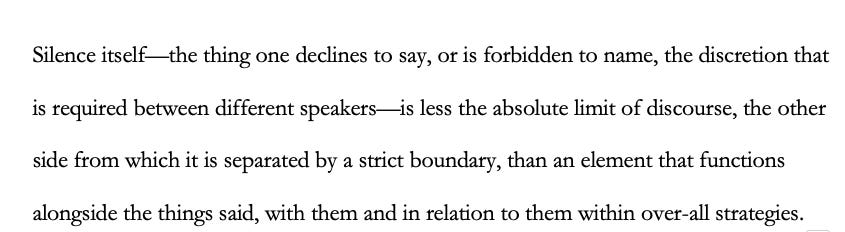

Foucault went as far to argue there is no real difference between language and silence:

Since ‘discourse’ is Foucault’s term for the many ways society wields power over its members, when he writes that there is no boundary between silence and discourse, he suggests that silence is also a part of the oppressive system that will not allow truths to be communicated – if such truths even exist. He goes on to write that silences ‘are an integral part of the strategies that underlie and permeate discourses’. For Foucault, silence is another form of language, an element to deconstruct, a place to find meaninglessness; for him, silence, like words, is a slippery medium from which meaning cannot be found or communicated.

How does this rather nihilistic approach apply to poetry? I believe there is a hole, so to speak, in the post-structuralist methodology: it does not take into account that poetry inherently both embraces the post-structuralist view and transcends it—poets who employ the poetics of reticence know that language and silences are limited and work from that knowledge. The poetics of reticence involves strategies that address the very real inability of language to communicate.

I believe that the poet’s goal is to embrace the notion that words are insufficient and also that a strategic use of silence produces what Mark Dow has called the ‘tip of the tongue phenomenon’ which is ‘this feeling of knowing something we cannot put into words’. The infinite well of ideas, emotions, and messages that exist within a poem, may remain inaccessible to the reader yet can be sensed palpitating under the surface.

Silences are everywhere in a poem—even inside the words, and these silences approach unsayable truths about the sublime, and the beginnings of time itself.

Poets know that language fails. And we write from that awareness. When this process is embraced, inexplicable phenomena can happen. I find this consciousness (this embracing of the limits of language while simultaneously generating meaning from this knowledge of language’s limits) profoundly present in the poetry of the Egyptian Jewish French writer Edmond Jabès (1912-1991). His poems are filled with questions, conversation, snippets of narrative, and mysterious observations all of which suggest humility, uncertainty, knowing that one can’t know. At the same time, his poems reach out to the reader and somehow communicate crucial messages, which lead to more questions…

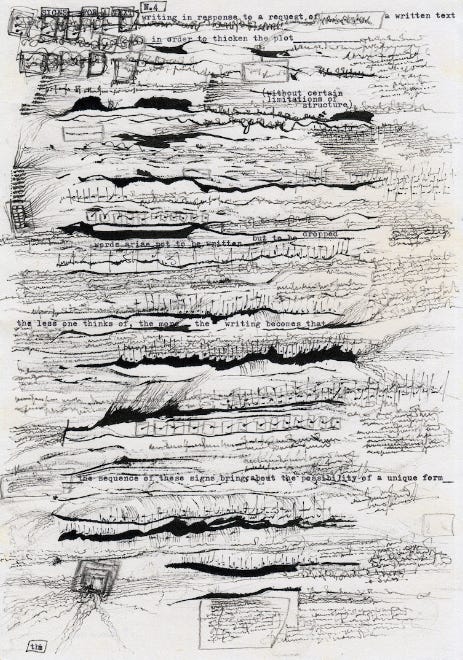

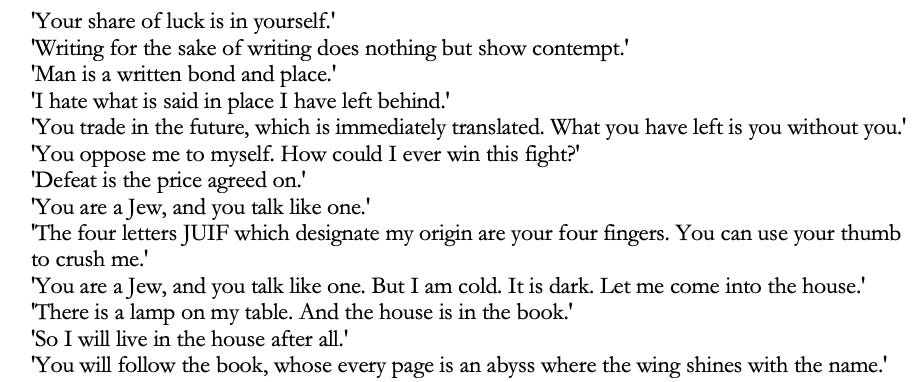

Artwork by Federico Federici. Writing in Response to a Request of a Written Text, pencil, ink, pigment liner, 2024 (Rome: Private Collection)